- AE Golf Performance Newsletter

- Posts

- Grip Strength and Golf

Grip Strength and Golf

Grip Strength and Golf

Intro

Welcome back to the AE Golf Performance Newsletter. It’s been a while since the last post, but we’re back with a topic that I see discussed often: how important is grip strength for golf?

While this seems like a simple question, there are a few conflicting viewpoints on the topic. One saying that grip strength is critical for swing speed, and another saying that correlations between clubhead speed (CHS) and grip strength are confounded by the fact that grip strength is a proxy for overall muscle strength (e.g., strong people in general tend to have strong grips).

In my opinion, both sides can be true to an extent. Grip strength can be both directly valuable for golf and CHS, while also acknowledging that its relationship with CHS can (and probably is) confounded by other factors when using just simple correlation analyses.

But saying both can be true is not particularly helpful, so I want to dive into the topic and give my perspective on each side of the argument and give some thoughts on what it means from a practical standpoint.

Background on the Topic

The hands are the connection point between the golfer and club, and the club’s motions are dependent on the amount, direction(s), and timing of forces/torques that we apply to the grip throughout the swing. It shouldn’t be surprising that how you grip the club is considered a fundamental aspect of golf technique.

But when it comes to how much grip pressure you need, you’ll hear contrasting opinions. For example, as a young golfer, I had the Sam Snead quote thrown at me often:

“Hold the club as if you were holding a baby bird.”

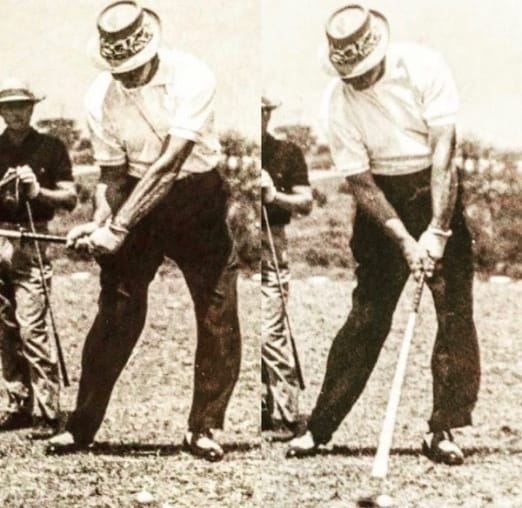

I (and many other golfers) took this quote to mean you needed to hold the club lightly. But we know that to swinging fast requires a lot of force to be applied to the club at various parts of the swing (more to come on this below). And it’s worth noting that Sam Snead was often described as being quite strong, particularly grip strength.

You can see that strength in action in the image below.

Photo Credit: Mark Immelman Twitter/X (https://x.com/mark_immelman/status/1232444270449086465)

So, what’s going on? I think this quote is often oversimplified and misapplied by golfers. Sam’s strength combined with his ability to skillfully apply forces at the right times, in the right amounts, and in the right directions likely allowed him to put large amounts of force into the grip at specific parts of the swing, while also having the overall feel of being relaxed and tension-free. In contrast, less skilled golfers often have less total capacity (e.g., max grip strength) and skill in terms of applying that grip force within the context of the swing. The result is that it feels tense and higher effort to maintain control of the club.

But with that in mind, let’s dive into the two sides of the grip strength argument.

Grip Strength as a Predictor of CHS

Several studies have found a positive linear correlation between a golfer’s grip strength and their CHS (Wells et al., 2009; Hellstrom, 2008). This has been used to justify the view that the golfer should specifically focus on increasing grip strength to gain swing speed. While I believe there is some value in grip strength for golfers (see sections below), there are some issues with this interpretation.

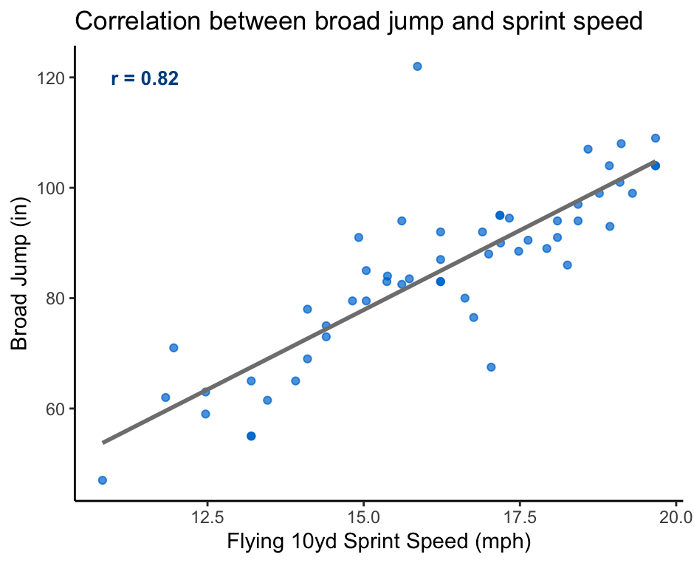

We first need to understand what a correlation analysis is doing. In most cases, a Pearson’s correlation coefficient is being calculated. This statistical method is used to determine the strength of the linear relationship between two variables. You test a sample of golfers for both grip strength and CHS. You then quantify the degree that golfers with higher grip strengths also have faster CHS.

See the example below with some non-golf athlete testing from a few months ago, showing the basic relationship between broad jump and sprint performance measures.

Example of a basic correlation plot using data from testing I helped coordinate for middle school and high school athletes. In this case, athletes that jumped further during a broad jump test also tended to sprint faster during a sprint test (though there are exceptions and outliers).

While this is useful, you need to understand what it does and does not tell you.

A correlation analysis generally tells you that two variables are related in some way, at one specific timeframe and across a specific sample of golfers. Without more context, we cannot assume that if a golfer increases their grip strength, that it will lead to more CHS unless we have a strong understanding of how and why the relationship exists. In other words, “correlation does not equal causation.”

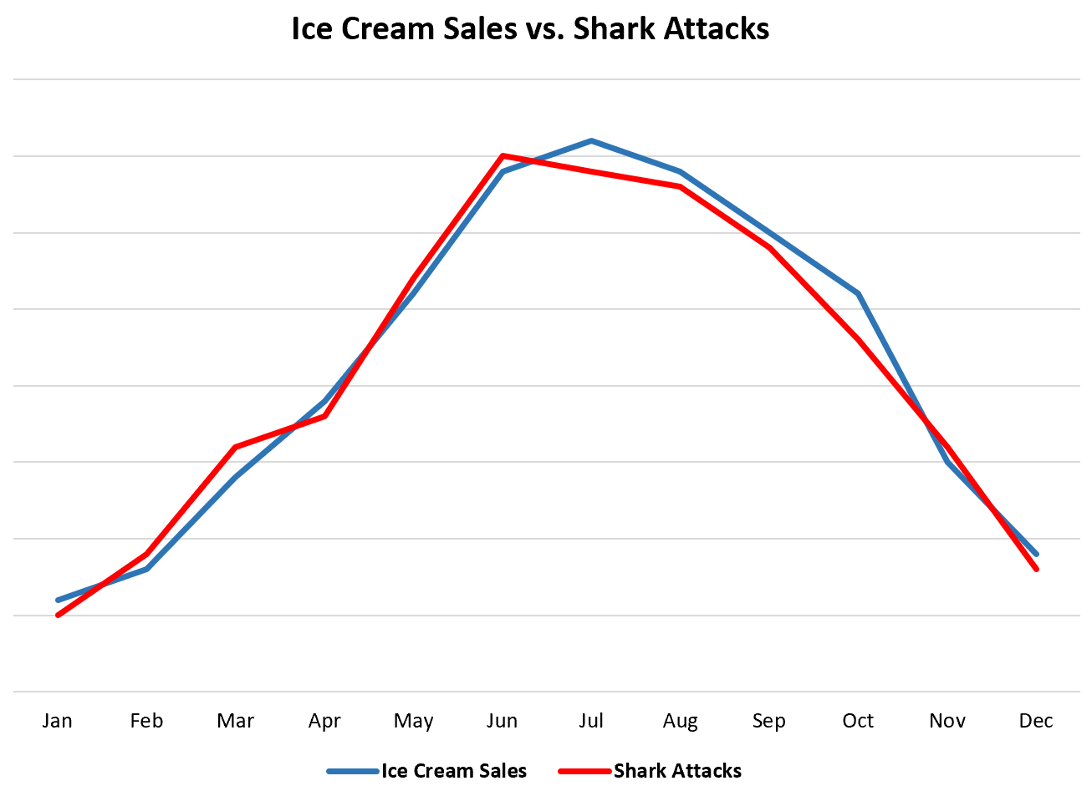

On that note, simple correlations can sometimes be explained by other variables. Let’s take a classic example: the relationship between ice cream sales and shark attacks. Higher ice cream sales are associated with increased shark attacks. So, does eating more ice cream increase your risk of shark attacks? A more likely explanation is that a third variable is explaining the relationship. When it’s hot outside (like during the summer), people are more likely to buy ice cream AND swim in the ocean. So, both variables increase at the same time, but not a directly causative manner.

How does this relate to grip strength and swing speed? Well, it’s possible that the relationship between these two variables is being affected by other factors as well. An important one is that grip strength is a proxy for overall muscle strength and power.

For example, here is a quote from a review article on grip strength and healthy aging (Kozokai, 2017):

“Grip strength, which represents hand strength, has been adopted as a useful indicator of muscle strength. Since grip strength is strongly related to lower extremity muscle strength, as well as overall body strength, it has been referred to as an indicator of muscle strength for the entire body. “

In other words, people that are generally strong tend to also have a lot of grip strength. This is a major reason why grip strength is often used as a quick and easy measure of neuromuscular strength in studies on longevity or population-level analyses.

Given that measures of lower and upper body strength and power tend to be strong predictors of CHS, it could be that at least part of the relationship between grip strength and CHS is being driven by the fact that strong and powerful golfers happen to be good at both grip strength tests AND swinging a golf club fast.

BUT this also does not mean the entire relationship between grip strength and swing speed is just due to this statistical confounding. I do think there is a strong likelihood that grip strength has specific benefit for golfers, even if the relationship is smaller or different than what is often reported.

Let’s go through why this may be the case.

Making a Case for Grip Strength

There are only a handful of forces that act on the golf club during the swing, with the ones coming from the golfer being by far the most important. And the sole connection point between golfer and club is at the grip. This is why the total work that a golfer performs on the grip along the hand path is a near perfect predictor of how fast the club will be moving during the downswing (Mackenize et al., 2020). Everything we do from a technical and physical training side is to improve or modify the timing, direction, and/or magnitude of forces that we apply to the club through the grip.

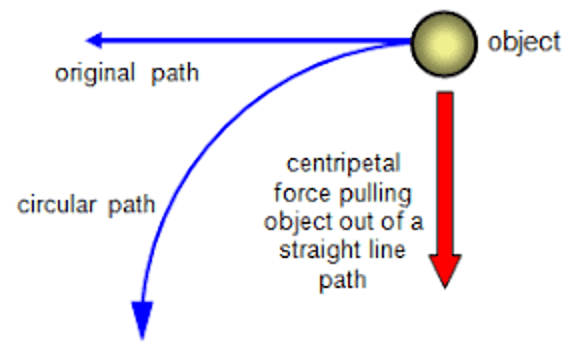

An under-appreciated component of the golf swing is how much grip pressure is needed to control the momentum of the club’s rotational path, especially as it reaches high speeds near impact. Why? An object like the momentum of a moving club wants to keep moving in its current direction unless acted on by a force to help maintain its rotational path.

For example, if I pulled the club down from the top of the backswing and then immediately relaxed my muscles, the club would not rotate around me and into impact with the ball. Instead, it would move straight down in the direction of that initial pull and likely fly straight into the ground (or hit me on its way down).

Golfers are constantly applying force along the length of the club to control the rotational momentum of the club and to carve out its path into impact with the ball.

Dave Tutelman did a very in-depth article on estimating the amount of grip force required to keep control of the club at different swing speeds. For those that want the full breakdown, check it out here: https://www.tutelman.com/golf/swing/gripPressure.php

But here are a few summary points:

- The grip force needed to maintain the club’s rotational path is dependent on the mass of the clubhead and shaft, the radius of the rotation (which is affected by the length of the shaft), and the speed of the clubhead.

- Tutelman also accounts for the friction between the hands/glove with the grip, and the taper angle of a typical golf grip, which affect the required grip force.

- With these factors considered and using typical values for the properties of the club and grip, he estimates a 110-mph swing requires ~110 lbs of force, while a long drive caliber swing speed requires 180+ lbs.

This aligns well with other attempts at quantifying hand forces during the swing. For example, Miura (2001) conducted a modeling study on the “pulling” actions that skilled golfers perform through impact. Overall, their model suggested that a swing of ~112 mph with a well-timed pull on the grip through impact would involve over 120 lbs of hand force.

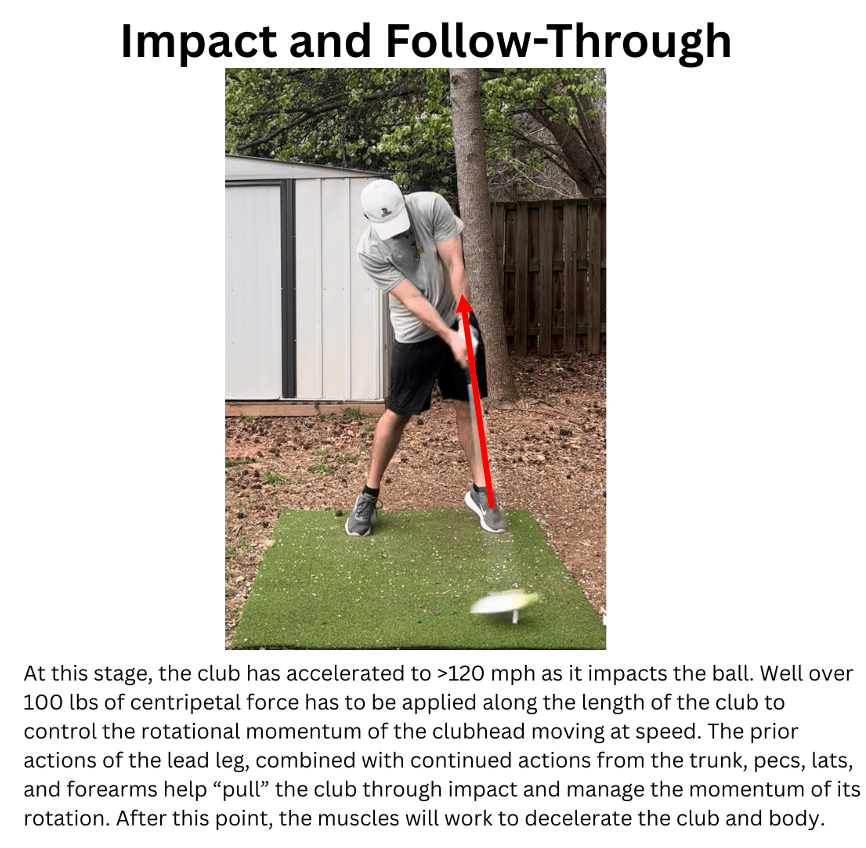

Skilled golfers will generally use a coordinated action of the entire body to create this pulling action along the shaft (see visual below with my swing). The jumping action that you see some golfers perform (and you can see in my own swing above) is serving several purposes, but I believe a major one is that it helps to counteract the momentum of the club and create the centripetal force necessary to maintain its path into impact with the ball.

While the source of this centripetal force stems from a coordinated action across several body regions, the grip is the final link of the kinetic chain and could be a limiting factor if trying to swing at fast speeds (and control the club at those speeds).

Perhaps even more likely is that having considerable strength across the body, including the grip, allows for that hand force to be applied to the club at lower relative percentages of your max effort. Allowing you to produce the force necessary to control the momentum of the club without feeling like you must exert maximal effort to do so.

Okay what do I do about it?

So far, we’ve talked about two sides of the equation:

1. Correlations between swing speed and grip strength could be (at least partially) confounded by the fact that grip strength is often a proxy for overall strength/power.

2. Grip strength may still play an important role, since to swing fast you must be able to put a lot of force into the grip of the club at key points of the swing. Being able to apply that required force at relatively low levels of effort may be particularly advantageous.

Regardless, having a strong grip is generally a good idea. And because grip strength is relatively easy to assess, you can test and monitor it alongside other strength/power measures.

If you’re not currently training, a well-rounded training program should usually be the priority. Whether your goal is maximizing speed, injury risk reduction, or simply general health, this is going to be the big bucket to fill from a physical training perspective.

Oftentimes, grip strength will naturally increase as you train, since it is loaded indirectly through many strength exercises (e.g., rows, pull-ups, deadlift variations, etc.), or even when simply racking and un-racking weights. You can just monitor grip strength periodically to make sure it is trending up alongside other strength and power measures.

If you are already training and grip strength is lagging behind other areas, then you can add in a few direct grip/forearm exercises (e.g., Farmer Carry, plate pinches, etc.). But be mindful of the total workload you apply to the grip. It can be easy to end up frying your grip/forearms if you are hitting it with a combination of direct grip training AND high grip requirements from general strength work. Like training any other aspect of your body, we want to have proper progressions and manage volume appropriately.

In other words, you can test your grip strength and see if it’s a glaring weakness relative to muscle strength in other areas (lower body, upper body, etc.). If so, and you’re not currently training, then a well-rounded training program will often elevate strength across the board, including the grip. But if grip strength lags behind other measures, then you can always add in a bit of direct grip/forearm work to bring that weakness up. Alternatively, some golfers may just prefer to have a bit of direct grip/forearm work in from the start. That is just fine, as long as the volumes are not excessive to the point where you are regularly dealing with grip fatigue/soreness during your golf.

Working on Applying Grip Capacity to the Golf Swing

It is worth noting that how we interact with the club during the golf swing is different than the grip requirements during grip strength assessments or gym-based training exercises. And the golf swing is not just about how much force, but also applying it at the right times and in the right ways to accelerate the club effectively (which is highly dependent on how your body moves to transfer momentum to the club, through the grip). So, while gym-based direct and indirect grip work can increase grip strength capacity, you also want to learn to apply that capacity to the specific demands of the golf swing.

I believe that speed training work is a direct way of addressing the ability to skillfully apply forces to the club, alongside gym-based capacity work. For example, overspeed or max effort driver swings will overload the grip force requirements (since faster speeds require greater centripetal force). Additionally, altering the weight of speed sticks or clubs will modify the force-time characteristics of how you apply force to the grip.

But this is a topic for another day since we’ve already gone far enough for one post!

Summary/Conclusions

Overall, I believe a few things can be true simultaneously:

1. The simple correlations between grip strength and swing speed are likely at least partially confounded by the fact that grip strength is closely linked to overall muscle strength and power.

2. It is also likely important to have sufficient grip strength, given that the grip is the connection point between golfer and golf club, and the force requirements at this site can be relatively high when swinging fast.

3. Even if many golfers can put the minimum necessary forces into the grip, being able to do so at lower percentages of max effort is likely a performance advantage.

4. General strength training often increases grip strength as a natural byproduct. But by simply testing grip strength alongside other strength measures, you can confirm that this is the case. If grip strength is lagging behind other areas over time, it is simple to add small doses of direct grip work to a program to address that gap.

5. Grip strength capacity is one thing, but the ability to skillfully apply forces at the right times and in the right ways during the swing is another. Technical and golf-specific speed training work can help here.

References

1. Hellström, J. (2008). The relation between physical tests, measures, and clubhead speed in elite golfers. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 3(1_suppl), 85-92.

2. Kozakai, R. (2017). Grip strength and healthy aging. The Journal of Physical Fitness and Sports Medicine, 6(3), 145-149.

3. MacKenzie, S., McCourt, M., & Champoux, L. (2020). How amateur golfers deliver energy to the driver. International Journal of Golf Science, 8(1).

Miura, K. (2001). Parametric acceleration–the effect of inward pull of the golf club at impact stage. Sports Engineering, 4(2), 75-86.

5. Wells, G. D., Elmi, M., & Thomas, S. (2009). Physiological correlates of golf performance. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(3), 741-750.

WHILE YOU’RE HERE

SUBMIT REQUESTS, QUESTIONS, OR FEEDBACK

If you want to work with me, have questions, or recommendations for future content, follow the link below and submit a response. This link will be available on every issue of the newsletter, so you will have opportunities to do this in the future as well!